Written together with Dr Moshe Sokolow, author of Pursuing Peshat: Tanakha Parshanut and Talmud Torah

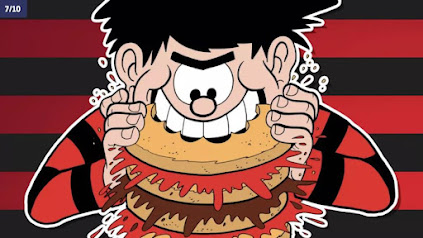

Are Cheeseburgers Kosher?

Students will typically respond to this rhetorical question correctly – that cheeseburgers are not kosher. They are less comfortable, however, with the follow-up questions: If the Torah wanted to prohibit them, why is there no verse saying, “Thou shalt not eat cheeseburgers”? Why is the closest we can get to it, “Do not boil a kid in its mother’s milk”?

These questions are entrée to the consideration of the two most crucial issues in interpretation. First, why not assume that everything in Tanakh can be understood literally? Second, if we are persuaded that it cannot always be taken literally, what makes an interpretation acceptable?

The answers to both questions are straightforward. If the Torah were to legislate for every conceivable situation we might confront, it would have to be the length and complexity of the Mishneh Torah or the Shulhan Arukh, and even those two legal compendia are incomplete without the myriad commentaries and responsa that accompany them. To compensate for this shortcoming, the Torah is “polyvalent” (having many values), allowing for multiple interpretations and applications, that are judged by their fidelity to the linguistic traditions of the people who regard these works of literature as “sacred Scripture”. The first part of Pursuing Peshat, on which we will focus here, traces these two issues through a millennium of biblical exegesis (parshanut hamika), from Se`adya Gaon in the 10th century through R. David Zvi Hoffman at the start of the twentieth. Some—including Se`adya and Ibn Ezra—addressed these questions explicitly in the introductions to their Torah commentaries. Others—like Rashi and Rashbam—whose literary style did not include introductory remarks, dealt with them in practice.

Here is how Rashi and Rashbam might handle our cheeseburger question.

Exodus 23:19, “do not boil a “gedi” in its mother’s milk.” Rashi, following in the footsteps of the Talmud and Midrash, interpreted gedi as any young animal, and deduced the additional prohibitions against eating and deriving pleasure, from the verse’s threefold repetition. In other words, working back from the given conclusion that cheeseburgers are prohibited, Rashi would justify that ruling exegetically.

Rashbam, however, found Rashi’s explanation problematic. If any young animal is intended, why specify a gedi, which is specifically a kid, and why does this clause always appear in the context of the three pilgrimage festivals?

His answer: “Scripture addresses reality” (lefi hahoveh dibeir hakatuv). Kids were indicated because they are usually born in pairs—with one designated for sacrificial purpose—and are rich in milk. The link to festivals, too, is a nod to reality since that is when people eat the most meat. And yet, citing Talmud Hulin, he concluded: “This is the rule regarding all meat and milk.” In other words, while Rashbam disagreed with Rashi in exegetical theory, he accepted his implementation in practice.

Talmud Reclaimed also draws upon this prohibition in order to contrast the approaches of two different Rishonim, Rambam and Ibn Ezra, as part of its exploration on which laws and interpretations are regarded as Sinaitic and which were developed subsequently by the sages and Sanhedrin.

In his discussion of this prohibition against boiling a goat in its mother’s milk, Ibn Ezra speculates as to its reason and suggests that, at its core, it is to be categorised alongside other “cruelty-mitigation” commandments such as not taking the eggs of a mother bird in her presence and not slaughtering a parent animal along with its offspring on the same day. Viewing the basic biblical prohibition as relating specifically to the boiling of a goat in the milk of its mother, Ibn Ezra (in a similar vein to Rashbam) writes that it was formerly common to eat goat meat – which typically has a dry texture – together with milk.

Crucially, he then suggests that the expansion of the original biblical prohibition against boiling goat meat in its mother’s milk so that it covers all forms of meat and milk is a rabbinic ruling based upon the principle of being stringent in matters of doubt over biblical law. Whether Ibn Ezra views the broader prohibition of cooking meat together with milk as purely rabbinic or as rabbinically legislated Torah law can be debated; what is clear, however, is that he does not regard the prohibition as belonging to the body of transmitted and immutable Oral Torah traditions. This would therefore potentially allow it to be revisited by a future Sanhedrin.

Rambam’s treatment of this law, by contrast, presents the oral tradition’s expansion of the prohibition against cooking goat meat in its mother’s milk so as to apply to the cooking together and eating of all types of meat and milk as an immutable transmitted Sinaitic teaching:

The Torah states: "Do not cook a kid goat in its mother's milk." The received Oral Tradition, teaches that the Torah forbade both the cooking and eating of milk and meat, whether the meat of a domesticated animal or the meat of a wild beast.

So integral and immutable is the oral tradition’s interpretation of this verse that “if a court will come and permit partaking of the meat of a wild animal cooked in milk, it is abrogating the prohibition not to detract from the Torah”. Rambam’s understanding that the expansive interpretation of the prohibition against cooking a goat in its mother’s milk is of Sinaitic origin is consistent with the approach taken in his Introduction to Commentary on the Mishnah, that Moshe clarified key definitions and components of the commandments when he taught the Torah’s text.

Nevertheless, we are left with the question of why the Torah presents the prohibition so narrowly in its verses, if an immutable Sinaitic tradition requires it to be construed so broadly. The answer to this may lie in the Moreh Nevuchim, where Rambam identifies a reason for the prohibition – distancing from pagan ritual – which relates most directly to the practice of seething goats in their mothers’ milk.

We therefore see a range of interpretive approaches by the Rishonim to this highly instructive prohibition. From Rashi, who appears to read the Oral Tradition’s conclusion back into the text to identify its peshat to Rashbam, who recognizes the inherent tension between the peshat and the transmitted tradition. And finally Ibn Ezra who appears to move in the other direction, reinterpreted the transmitted tradition in light of the simple meaning of the Torah’s text.

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Save 25% with promo code Peshat25 at kodeshpress.com

Peshat literally means the simple, or literal, interpretation of the text. However, the definition and determination of peshat is anything but straightforward. The Sages of the Talmud and Midrash debated how to ascertain peshat. This debate continued among the Rishonim and Acharonim: how much weight should be given to peshat as opposed to allegorical and halakhic interpretations, what assumptions inform us in arriving at peshat, and how do we differentiate peshat from derash? These debates rage into the modern day, as leading rabbis, educators, and scholars seek to understand the place of peshat in the nexus of biblical interpretation.

First posted yesterday on Facebook, here.